The Small Business Owner and COVID Lockdown Protestor Who Wants *More* Government

In the headlines, Dave Morris is just defying COVID-19 restrictions. In reality, he's asking for a better government.

“We got a government that has taken the stimulus money, they gave it to special campaign donors, they gave it to special interests, they abandoned me, and they have put me in a position where I have to fight back, okay?”

“You could’ve given me money and I would gladly walk away for sixty days and let this virus settle down. I’m not gonna do it alone.”

“This is a conspiracy, this is a tyranny.”

“Stand up America, give us the money to shut this thing down, but don’t take it out on a select few.”

Dave Morris, owner of D&R’s Daily Grind cafe, is not afraid to say what is on his mind. He is curious though, whether anyone in power cares to listen. Though the Portage, Michigan business owner has garnered a good deal of attention since his impromptu broadside against the government and COVID-related shutdowns went viral, his curiosity remains justified. Because while figures like Tucker Carlson and Matt Walsh implicitly tokenize Morris as some sort-of anti-government warrior, it appears that the substantive frustrations of Morris – and millions of other people in this country – remain unheeded. In reality, these frustrations stem from the government not serving as a guarantor of adequate material conditions for its people.

“I see the things we've lost since I was a young man raising my children – pensions are almost non-existent for the normal working man, healthcare is non-existent. 12 years, I can't afford it, Affordable Care Act – not affordable,” Morris laments. “So we rely on our health, I got good health, my wife’s got good health. And we, you know, look up and say thank you once in a while, see? But we've lost those things that we used to get.”

Morris found himself slipping into disenchantment decades ago, as he breached early adulthood. Reflecting back, Morris feels he came of age with lackluster guidance. But he recalls finding renewed purpose after meeting his wife, and his father-in-law. Morris found solace in his father-in-law, as a figure who was able to persevere through similar hurdles growing up, serving in the military before becoming a GM supervisor.

Feeling inspired, Morris found work as a salesman at General Telephone Company. This would be short-lived, however, as Morris was laid off a year and a half later, amid the deregulatory regime of President Ronald Reagan; on top of that, Reagan codified unemployment benefits as taxable income. This was an early moment in what became an ongoing reckoning for Morris, to question what his place was in the world. “I had a wife and second child on the way, and boy I said, ‘wow, what happened?’ So that was my first kind of blow with ‘why do they gotta treat me like that?’” Morris finishes with a tired chuckle, before continuing to trace his journey. As Morris describes his amble through the wayward American path, he speaks with the certainty of someone who is no stranger to disappointment, and the hustling tempo of someone who is trying to get as many words out into the world as possible – lest he loses this newfound willing audience.

After being laid off from General Telephone, Morris regained his footing, working at a smattering of small companies before finding a job in sales at the American Tobacco Company in 1986, when he was twenty-five years old. Eight years passed, and Morris rose to State Manager – complete with a company car, and financially-supported relocations and home purchases.

His family would transfer to Minnesota. Just months later, it became evident that the company would be sold to Brown & Williamson, a larger competitor that even still was shadowed by the commanding market force Philip Morris. At this point, Morris knew he would not have a job much longer, and soon left the company.

It was then 1994, and Morris found work at auto industrial company American Axle & Manufacturing in his hometown of Three Rivers, Michigan. Working as a welder without health insurance for $12.50 an hour, Morris again wondered “what just happened?” But it was a job nonetheless, and he proceeded to get involved in the plant’s union, aspiring to represent the membership better. After fifteen years at the plant, Morris became immersed in the 87-day-strike of 2008, negotiating as Chairman of the Local 2093 UAW union. Workers were striking in response to a proposed agreement from the company that would dramatically cut wages in varying degrees based on each plant’s location, and permanently close plants in Detroit and Tonawanda, NY.

Morris found himself in a disjointed blur. “I watched my union whipsaw two plants, one against the other, us against Detroit. And I can't go out and make the extra income...we were living on $200 a week strike pay. And we had members that could actually go out and make cash payment, good cash money and supplement themselves. I'm over in Detroit negotiating and can't do that,” he says. Nonetheless, Morris was committed to keeping the Union membership informed throughout the strike. He says he would call the union hall every Wednesday at a set time for a conference call with local membership, defying the national union leadership, who forbade him from discussing the evolving terms with others.

A plaque given to Morris commemorates his advocacy during the 87-day strike against American Axle & Manufacturing in 2008. The plaque specifically recognizes Morris’ commitment to keeping the union membership informed, in defiance of the national leadership. (Photo courtesy of the Morris family)

Morris was caught in a difficult situation. As he told Reuters at the time, he felt effectively locked out of the negotiating room for three weeks before the tentative agreement was even struck. His Three Rivers plant was slated to receive the lowest wage rates out of all the American Axle plants. Facing both disjointed negotiations and the looming threat of the Three Rivers plant potentially joining the list of plants being shut down, Morris was locked up. Given this ultimatum, Morris had said if other plants rejected the agreement and Three Rivers accepted it, their plant would likely need to break ranks in order to avoid even more layoffs.

“I was angry at the Union. I got one plant started at $13.15 an hour, and our plant was down to $10 an hour,” he recalls. “And that was the agreement they made: this plant over here gets to keep their pensions, ours are frozen. That's not unity. And that upset me. So I didn't figure I was going to get along there much longer. And I took the buy-out.”

Reflecting on his union experiences, Morris expresses disappointment in a structure that sometimes seems to absorb people into behaving akin to the kind of figures unions typically rally against. “When they've got a big, huge facility up in northern Michigan, and they've got a big place on Black Lake and every time a union president retires, they build him a cabin on that lake…this isn’t what Walter Reuther fought for, I can tell you that. You have lost your way because you've sold out on your membership who is losing their pensions, their pay, their jobs. And you don't want to do anything about that. You just keep raising member dues,” Morris groans, referring to controversy surrounding allegations of union executives spending membership fees and money from Detroit automakers on personal luxuries.

With his buy-out and disenchantment in tow, Morris and his family would sell their home in Three Rivers, purchase a cafe, and commit to their new life in Portage, Michigan.

Morris pictured in 2012 with his wife Rittia, and (left to right) children Austin, Hollie, and Brandon. (Photo courtesy of the Morris family)

Morris and his D&R’s Daily Grind Cafe join a barrage of people and small businesses across the country facing confusion, disappointment, and the looming threat of closure amid the COVID-19 crisis. The government’s Paycheck Protection Program has been under constant scrutiny as reports have shown massive blunders intrinsic to the program: banks prioritizing loans for long-standing clients; larger businesses acquiring disproportionate aid over smaller businesses, due to banks’ incentives to collect bigger fees from bigger loans; much of the assistance that has been dispersed successfully still being delivered with numerous strings attached. These and other inherent flaws to the PPP have dogged millions of people, particularly poorer or minority communities who bear the brunt of not only the medical threat of COVID-19, but also these issues of access – by ways of explicit discrimination, or not being among wealthy or well-connected bank clients.

Morris – though not facing the historically-embedded obstacles minorities face – has still encountered problems that millions of people across the country relate to. His frustrations speak to aforementioned issues: logistical hurdles, who gets preferred access, and what the purpose of the government’s aid programs were in the first place.

“Well, they just sent me and my wife for $1200. We didn't get it ‘till May because I didn't have the direct deposit into an account,” Morris says, referring to the one-off stimulus checks doled out by the government months ago. “And then when it came time for the loans – I knew they approved it on Friday, I had my paperwork submitted Monday, and then Tuesday they told me ‘sorry, the funds have been depleted.’ And I had to wait for the second one to come right around the corner. And then the calculus, I don't know what happened between me and my bank – the numbers weren't what I thought they should be,” Morris explains. His frustration relates not only to the shock of the system in having millions of people applying for aid all at once, but also a lack of transparency in having loans doled out through middlemen.

“Personally, I thought when we went through the SBA, that was the wrong move. Okay. It all stayed up at the top – it went to people that already had their accountants and their bankers and their lawyers all in the same room. They had hashed out prior to it even being approved – all the guys had to do is walk in and sign, and they got their money,” Morris says. “And for us guys left behind, well, we don't really have them kind of guys working for us. All they were really trying to do was keep the employees off the state unemployment system. That's how I felt. You got to keep this guy employed, you got to do this, and then you gotta use it for fixed cost utilities. And I thought, well, you know, that's not doing much for me when still we're in the to-go process all summer.”

The insufficient loan program left Morris to scramble for other solutions. He gave up and pulled money from his own retirement account.

The government’s aid response has served as one of numerous exhibits in recent memory that have called to question America’s status quo of means-tested, siloed government programs. These shortcomings challenge basic characteristics of American federalism, given that localities are charged with delegating COVID-19 shutdowns, but have no intrinsic means to support people once those shutdowns are enacted. Morris, in the viral interview, proclaimed he would have gladly walked away from his business for sixty days to allow the virus to settle down, as long as the government would have paid him to stay closed. But he refused to take those measures alone and without support from the government. Morris joins many who wonder how a country with 4% of the world’s population holds around 23% of the world’s COVID-19 cases; how the same country holds almost 19% of the world’s COVID-19 deaths.

“I almost feel like I'm living in the greatest country in the world, and we just handled a pandemic worse than any of them.”

What does it mean to live in the “greatest country in the world” while facing the blight of functionally inadequate governance? Morris bemoans the government’s failure to not commit to decisive, universal action. “You start calculating $2 trillion by maybe 120 million households in this country. And it's a pretty good number that you could have given the American people, you could still do it today. Go around these organizations and corporations that want to hog the money and give it to their friends. That's what we got to do. And we’ll gladly go back and say ‘hey, it's time to get a grip on this virus. We're tired of it spreading and killing the elderly. We don't want to do this our society, we could have handled this so much better.’”

At the end of the day, Morris hopes mistakes are not repeated. “We need that type of universal policy in this country. Let's learn something from this thing. These viruses are going to continue to come, and this isn't the answer: shutting down segments of the economy, and different states, different rules,” he says.

What, then, of the “conspiracy” Morris was lambasting in his interview-gone-viral? For him, the conspiracy is not about the existence or suffering laid out by COVID-19 – rather, it is how those in power manipulate structures as they exist in order to benefit themselves and their associates. These notions of conspiring officials were grounded in concrete examples for Morris – such as the reports of alleged insider trading committed by multiple Senators and their family members. “We know they were inside trading for years. We've seen it happen with COVID. We've seen our senators and some people in very high, powerful positions bail out on one stock and grab another one and watch that baby go up 400% a month. I pay attention to those things and it infuriates me as a citizen of this country. It is not getting the exposure it should get and it bothers me.”

These scandals complement a Congress that has failed for months on end to provide relief for people. Now, after weeks of back-and-forth, Congress has struck an agreement for a package complete with dubious measures, $600 checks, and lack of local & state aid. Though the bill has now passed – after days of uncertainty due to President Trump’s initial refusal to sign it – that it took Congress months to reach such a relatively limited deal speaks for itself.

While Congress had remained incapable of promptly instituting a comprehensive program to address emergencies millions of people are facing – the loss of employer-tied healthcare; the imminent expiration of unemployment relief; the looming threat of eviction – they still found it within themselves to tie together a whopping $740 billion dollar military budget. “This isn't working. And there's two parties up here, really one party I fear. And it's just not working – and greed is going to destroy us from within,” Morris says.

Morris – whose grandfather served in World War II and whose father-in-law served in the military – moreover holds disdain for an American government insistent on being a global “bully,” while tabling the people’s well-being. “Everybody says you got to have a strong defense – how strong does it got to be, okay? We could get some money out of there and help the American people with healthcare maybe, right?”

America’s pervasion across the globe bothers Morris – not just because he finds it hampering America from solving domestic issues, but also in acknowledgment of other countries’ perspective. “I don't want to be the bully of the world – I don't want to police the world. We have taken that can of worms and just kept it open – we're still in Germany, we’re still in Afghanistan, we're still in Iraq. We think we got to be out there policing everybody….I understand why some countries hate us so much.” Morris’ words are particularly validated given recent news of President Trump’s pardoning of four Blackwater private security contractors convicted of killing up to 17 innocent people in Iraq, and shocking revelations of CIA-backed death squads conducting massacres in Afghanistan that have led to the deaths of at least 51 civilians.

Morris relates America’s ostensible bipartisan dedication to military spending more broadly to a two-party system hounded by money in politics. “I also believe, when it comes down to the candidate of the party, they all get to spend the same amount of money. There's no reason that money buys all the commercials, okay? There's no reason that this guy just spent hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars, where does all that money come from? And meanwhile, the guy down here that might be a better guy, he doesn't have the funds, so he gets snuffed out so early. I'd like to see a universal program that says number one: let’s open the door, we want to hear them.”

The combination of a largely two-party system and exorbitant amounts of money in politics is perceived to generate one of the primary obstacles to progress: being heard. Morris feels strongly about this. “You can't hear these people. They don't get on the debate stage, the media ignores them all. There's some very good individuals out there that could bring this country [together] – there’s gotta be 1000s of them. But because they don't attach to that corrupt two-party system, they don't get heard. They just get shunned.”

Why, Morris wonders, can media networks not be held accountable to provide equal and free time for candidates? Could the government at least negotiate with the networks to approach something that resembles equity? Though there is an “equal-time rule” that technically mandates broadcasters offer to sell equal air time to all candidates of a particular office, there is no mechanism that guarantees equal air time – what is mandated is access, not affordability or feasibility to actually take advantage of the opportunity. Interestingly enough, this dynamic distinctly echoes the debate surrounding government-provided healthcare.

Morris condemns exorbitant costs of medicine and healthcare generally in America. “The hospital can charge what they want, the pharmaceuticals can charge what they want. Everybody’s out to make massive profits. If you can charge $5,000 for a pill that I can get in Canada for $200, you have to ask where that’s going. It’s hard for me to believe we pay so much for insulin, and in other countries you don’t have to.” Morris is critical of rejecting government action while allowing insurance lobbyists to dictate policy. Consequently, he does not envision the fruition of national healthcare while greedy forces still pervade halls of power.

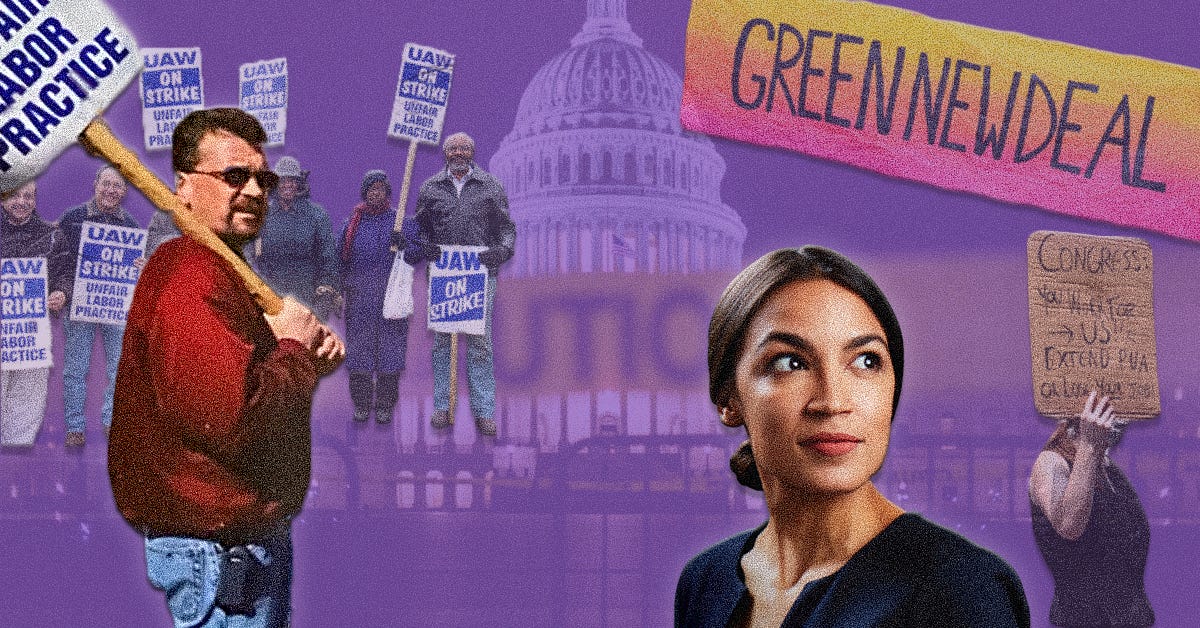

Morris does have someone in mind who, to him, displays how to govern without, and against, greed: Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

“You got to call those pharmaceuticals in the room and, and beat them over the head a little bit. I've seen Ms. Cortez do it a couple of times, I kind of appreciated the way she put them on the line. And she’s a very prepared person,” Morris says of the New York Congresswoman. “I’ve seen her go out there and go after them a little bit – it impressed me, okay? She's on point with some of the things she's saying – it’s just not getting heard.”

Interestingly, Morris speaks directly to how someone ‘like him’ is meant to hold specific feelings towards the New York Congresswoman. “She's a very smart person. She's very passionate, and she prepares herself very well. And it's hard to debate her – if you're going up against her, you better have your facts straight. And I did my own research, okay, I didn't let anybody tell me that she’s a silly, crazy person. I watched some of her debates and what she was talking about, I was impressed. Okay, I got no hard feelings towards her. I think she's a good person. And she's right on target with a lot of things she's saying.”

Morris’ words may sound surprising, if one were to only be superficially acquainted with him. But in actually interrogating the world-views held by someone like Morris, his approval seems quite rational. After all, Rep. Ocasio-Cortez’ belief that “it’s not just that we can be better, it’s that we have to be better. We’re not good enough right now,” sounds similar to something Morris himself could have insisted.

And Morris does in fact echo this rhetoric. “I just don't know why you and I can’t sit here and get a few other good people in the room, and it wouldn't be that hard to fix some of these things. And you know what, we could come out on fire, and we could get this country united and we could wrap our arms around each other,” Morris implores. “And you know if that was the only commitment to come out of that room, it'd be pretty easy to get ‘er done, buddy. The masses would come behind us and they would hear us.”

Morris’ respect for Rep. Ocasio-Cortez extends beyond rhetoric and into the policy landscape. Earlier, Morris explained how he does not associate Rep. Ocasio-Cortez with “this green idea and all these other things,” but when I press further specifically about the Green New Deal, Morris says he has not truly read the whole deal yet, but actually views it in favorable terms.

“I think there is alternative energy out there that needs to be looked at. The quicker we get there with it, then the better off we'll be. Again, get the big oil companies out of the business – I don't want to say put them out of business, but get their influence out of Washington, so we can expand these electric vehicles much quicker than what we're doing it at. You got that influence from lobby groups up there that prevents law from getting done. But I think there's some things in the Green New Deal that are probably good...and there's certainly going to be jobs with that, there could be plenty of jobs created. And we have to look forward to the elimination of the fossil fuels and oils and things,” Morris explains.

Especially when considering the rest of the world, a government project dedicated towards caring for the environment seems straightforwardly necessary to Morris. “There's things we can do to lower those emissions. You know, there is, and we all know that we shouldn't be 15% – we should be much better than 5%,” Morris says, addressing how America is responsible for 15% of the globe’s carbon dioxide emissions. “So that's a sad fact that I didn't realize it was still that high.” He mentions other countries’ willingness to embrace other forms of transportation as an example America could follow and provide facilities for. “We need to encourage, especially in the better climates, to do a little more walking and bike riding and public transit. That's a good way that we save on emissions, and we're just getting used to that – other countries, that's what they do all the time.”

Morris represents much more than frustration with the status quo. His belief in a politics that cares for people shines clear. His trust in the collective power of people to achieve that vision eclipses his own experiences beleaguered by disillusionment. “We’d really hear from some really good, qualified individuals out there that are capable,” he says. “I'll tell you, somebody’d rise out of them ashes and astound us all. It could happen. But we got to get that part of it fixed first. And it's going to take a new media outlet probably to get that done. It’s gonna take somebody that's committed to doing it. It's a big process, takes more than one.” Morris’ animated spirit is not reserved for today’s world, but also the world he will leave behind for the future. “I like to think before I pass, or on my deathbed, we made a better way for my grandchildren than where it was when I was in my 50’s. That's what we're hoping for.”

The timbre of Morris’ voice rings less like a dwelling upon the throbbing of this world, and more like a wonder about the buzzing of a better world. “We got to go out and hug one another one time. Okay, can we just try it? Can we walk out and shake your hand and say ‘I love you brother, I love you sister?’”

And this wonder, this yearning for a better world, beckons Morris to consider how he can play a role in striving towards this better world that feels almost palpable. “I’m venting on a lot of life's frustrations here in America – the ‘greatest country in the world’ – that I've experienced for the last 40 years, and these things are bothering me tremendously. If I can do something about that, and encourage people...by God, maybe I'm not going into my old age, feeling like I got nothing to do. And if we can get there, boy, I'd be elated for my grandkids.” Morris sounds visionary, focused. Determined not necessarily with exact direction of what to do next, but certainty that the way things are now is inadequate.

Morris’ frustrations with America’s political status quo – alongside the knowledge that a majority of people want at least a third major political party in the country – challenges stereotypical political analysis that often dubs only certain people as typical “swing voters,” or that monolithically assumes certain groups will always be “scared away” by particular kinds of politics. This challenge is especially crucial to acknowledge as large swaths of people in America actually agree with the seemingly transcendent political project Morris espouses.

The Green New Deal – a comprehensive proposition with the stated goals of urgently meeting the climate crisis, all while creating millions of jobs, renewing national infrastructure, and uplifting and preventing the future exploitation of marginalized communities – is broadly popular. An increasing majority of people believe the government has a responsibility to ensure everyone has health care coverage. People largely support cutting America’s military budget to fund programs such as fighting COVID-19, and investing in education, housing, and healthcare. A vast majority of people believe the American economic system unfairly favors the powerful.

Yet these and other popular ideas – such as an increased federal minimum wage and the legalization of marijuana – are yet to be actualized or dignified on a federal level. And this disconnect between popular opinion and material realities substantiates Morris’ perception of America being led by a political duopoly that largely caters to the interests of a few, while only a handful of leaders meaningfully attempt to seek recourse for the anxieties Morris and millions of other people intimately experience. In this way, Morris’ eagerness for a transcendent political project appears quite justified – but is largely not dignified.

Morris and millions of other people remain skeptical of those in power, and continue to wonder why masses of people cannot come together to build a government that takes care of everyone. If conventional media outlets and public officials cannot engage these feelings head-on and dignify them, rather than treating them as outlandish, Morris is correct in surmising the need to eagerly support a new wave of media and public officials.

Amid a moment of heightened contradictions and suffering, the standards and norms that have led us to this moment are being challenged. And the traditions of media and politics – and the way we ourselves engage with both – should be under no exception.

Hey there, before you go –

I hope you appreciated this article. If you did:

Share it with people you think oughta read it. Email, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram — wherever (find me on Twitter here!).

Subscribe for free. If you found this worthwhile, you’ll want to stick around.

Leave a comment below! This whole newsletter is concerned with people, and how we navigate and confront power & politics. How we are told a better world isn’t possible – yet how we can and do pursue one anyways. This project is enhanced with your thoughts, reflections, questions all coming together. I’d really love to see all your reactions turn into some good, solid conversation here.

Be well, take care, and love. A better world is possible.