The 17-Year-Old Athlete Risking His Future for Palestine

A story about the myths that support structures of power – and the spirited traditions rising against those structures

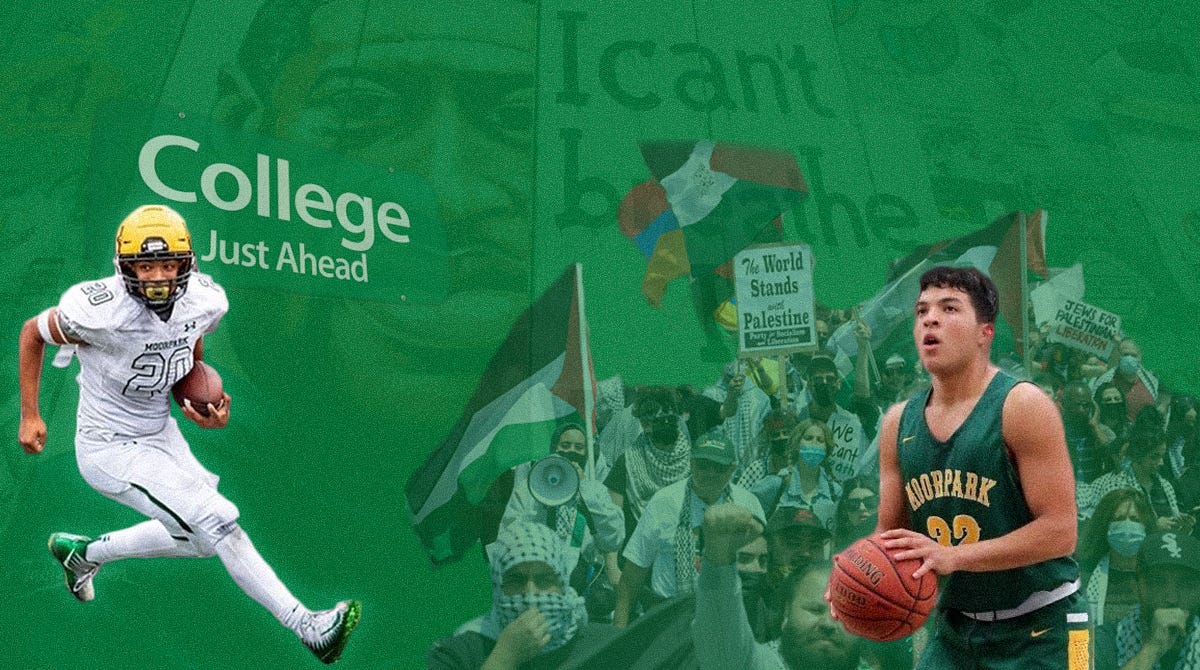

Omar Barakat is a 17-year-old high school student from Southern California who plays football and basketball. The youngest sibling of four, Omar plays tight end, defensive end, and linebacker on the field, and scraps up rebounds as a power forward on the court. He separated a joint in his shoulder last season, so he’s hoping to make a strong return to the field next season, especially in light of college recruitment.

Omar is Palestinian. Despite growing up in California, a place he has grown strong ties with, he feels just as much pull towards his family’s home – one he’s never been able to truly grow similar ties to. “The Palestinian struggle has been something I've been exposed to my whole life. My mom – she's an activist – and you know, she never had the opportunity to grow up in her homeland,” Omar tells me. When people ask Omar where he’s from, he’ll typically be met with confusion. “It's just unknown to people. It's been so many years of just ethnic cleansing and trying to get rid of the culture and people, and so many people don't even know about Palestine.” Trying to explain where Palestine is often just leads to more perplexion. “They'll say ‘Oh, you mean Israel?’ And that – that makes me a bit bitter.”

This bitter feeling came to head for Omar during the past weeks, as Israel continued forcibly evicting Palestinian homes, soon thereafter escalating as its security forces raided Al-Aqsa Mosque – one of the holiest sites in the Muslim world – no less during the conclusion of Ramadan. As Omar watched the violence unfold, he felt compelled to speak up, firmly announcing on Twitter where he stood:

Omar was not expecting much attention. He woke up the next morning in shock at all the support and comments he was receiving. “It makes me feel like the people are with me,” he says. “No matter how it affects my recruiting, I'm at peace.”

Omar’s public pronouncement came still before Israeli airstrikes obliterated a media building that housed offices for the Associated Press, Al Jazeera, and other media outlets. By the time of the official “ceasefire,” 256 Palestinians were killed, including 66 children (though a Palestinian doesn’t need to be a child for their life to matter).

The continually escalating violence inflicted upon Palestine is resonating with people in America differently than before, as this moment comes on the heels of a year when millions of people have marched and protested in support of racial justice and equality. People are identifying the through-lines between injustice in America and in Palestine, heeding Angela Davis – who has been drawing these connections for years – if not simply internalizing Martin Luther King, Jr.’s words that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Marches for racial justice in America laid groundwork for mobilization in support of Palestine.

The young athlete tapped into this newly-energized spirit in America. “When I posted that tweet, I didn't really think of it as ‘Oh, I have this power to spread my opinion and affect other people,’” Omar says. “A lot of people I wouldn't expect to support that tweet actually reached out to me. I've had a lot of people say ‘I'm not really educated on this. Can you explain this?’ I've had a lot of people I'm not even friends with reach out to me.” Beyond personal interactions, Omar is getting more formally involved as well, through organizations like the Palestinian Youth Movement.

Omar attributes his connection to Palestine to his mother, Amani Barakat, an activist for Palestinian rights who has worked with groups including Students for Justice in Palestine and Al-Awda (the Palestine Right to Return Coalition). “She’s at a protest right now, ironically,” Omar says with a chuckle. Omar recalls how much of his life has been spent surrounded by the “Palestinian struggle” – and how much of that was alongside his mother. “As a kid, I just remember every weekend I’d go to LA, go to San Diego, go to a Palestinian event. She really breaks her back for the Palestinian struggle. You know, it's an honor to be her son.”

Amani, born and raised in Kuwait as a refugee, moved to the U.S. in 1983. Amani felt fortunate compared to other refugees in Kuwait, as her family remained largely together. “My father's family was there. My uncles, my grandmother, we had a very loving family,” she recalls. However, this sense of security, felt as a refugee in a home that wasn’t home, was relative. “I did not understand why we needed to leave,” Amani says. “I remember him [her father] telling me ‘You're a Palestinian – we have a cause to protect and to advance. There's more to life than eating, and sleeping, and socializing with your family members.’”

People sometimes consider their identity in terms of lineages – of where they came from and who came before them. Amani’s father’s reasoning to leave Kuwait illustrates how Palestinian identity may differ. How can one ground themselves in where they came from, if where they came from is under perennial violation? Instead, identity may be grounded in sustaining it in the first place. “Let me tell you something. Being Palestinian is not easy. You know, because I feel like this is what we're fighting, we're fighting for our pure existence,” Amani says.

Omar (second to the left), his mother Amani (to the right of Omar), his brother (left), and his cousin (right) in Birzeit, Palestine in 2016 (Photo courtesy of the Barakat family).

Years ago, Amani and Omar were visiting Palestine. The pair had just driven away from a refugee camp for the day when they came across Israeli security officers confronting a young Palestinian boy who seemingly had done nothing wrong. The boy refused to answer the officers. The officers responded by beating him, breaking his tooth and causing him to bleed from his mouth. Young Omar protested without hesitation, yelling out the car’s window at the officers, pleading them to stop. Amani quickly closed the window and calmed Omar down, fearing the officers would target them next. This was not the first time the family had witnessed violence from Israeli officers, but this time impacted Omar differently than before. “Omar is not unique, other children are seeing this. And this is the conclusion they are drawing from the extreme violence that the kids are facing. We are holding on to our identity as well as our Palestinian-ity,” Amani says. “And we're not going to let go, because we're humans – no human would accept this kind of humiliation. But I'm telling you, this is where it all stems from – what we see and what we feel and what we experience. It's hard to not be Palestinian when you see all of that.”

This push-and-pull struggle to hold an identity so difficult to grasp, and the fortitude to claim it anyways, is borne out of soul-stirring duty, apparent from Amani’s reflection on all the refugee camps she has visited. “I've seen generations that were born and raised there. And when you ask them where they come from, they tell you exactly what village they came from, the story that their village went through, the names of the heroes that were protecting them. Their determination about returning and going back is something else,” Amani says. But such duty can place aching weight upon the keeper. “Honestly, I live with a lot of guilt,” Amani continues, with an edge in her voice. “I feel like no matter what I do, it’s not enough. You know, no matter how much I try to help, it's not enough. So, I feel protecting that identity is the least I can do.”

Amani ascribes her sense of obligation to Palestine with being a mother. “I always told my kids, ‘I became a better Palestinian because of you, I became a better person because of you,’” she says. She describes how happy she was to see Omar speaking out, as she never realized how vocal he might be for the struggle. “As a mother, this is what you hope and pray for organically to happen, like you don’t want to coach them.”

Contrary, or perhaps in addition, to how some people may view their lineages – as offshoots of personalities and genetics, vessels for tales and memories – the Barakat family tree seems to be passing down a specific tradition: conscious obligation. Omar, the youngest of the tree, says he was warned that speaking out on Palestine could hurt his recruiting. He didn’t care. “I feel as a Palestinian who never had the opportunity to grow up where I belong, it is simply my job to spread awareness, to do anything that I can to help Palestine be free one day,” he says. “My goal in life, honestly – it's just, I want my mom to see Palestine be free.”

And for Omar, lineal memories can be particularly impactful in what they bear. One of Omar’s uncles was born and raised in a refugee camp in Lebanon, and was never allowed to enter Palestine. Omar recalls going to a cemetery, alongside his uncle, to visit his grandfather. Omar harks back to something his uncle told him that day, that has stayed with him since then. “He was saying that when he dies, he wants to get cremated, and he wants all his ashes to be in Palestine,” Omar says. “And to me this – it really just hit the spot – it's really symbolic of so many things,” he continues, before pausing. He holds steady. “So many emotions I got from just hearing that.”

From Saffa Odah @safaa.art

To be Palestinian in America is to hold onto an identity that feels distinct, but one that’s challenging to define at all. “I've been stripped of the right to grow up in my land. I don't know how to speak Arabic. I don't know how to write in Arabic. The culture that I grew up in, it's been an American culture and not a Palestinian culture,” Omar says. He appreciates his upbringing, noting that he wouldn’t be who he was today without it. Still, he echoes the emotion I hear from his mother. “It's something that at the end of the day I regret, and it’s not even something I can regret because it's not in my control. I never had the opportunity to really be what I am. That's something that I think about often.”

Omar’s grappling with his identity – and his willingness to advocate for it – is not occurring in a vacuum. As Omar internalizes traditions and stories exchanged within his family, he’s surrounded by a cultural milieu reinforced largely with its own set of traditions.

America is a land of fantasy. If there’s one thing that keeps this nation tied together at the seams, it’s the trick of myth. The enduring reverberation of tradition in all corners, epitomized by pledges of allegiance to the American flag every morning in classrooms across the nation; students reprimanded for any flinch away from the ritual’s demand for fixed eyes on the flag and hands on hearts.

In short, schemes of myth and tradition fulfill America’s efforts to present itself as exceptional, as a beacon of democracy and freedom amid a cold, scary world. They also buttress efforts to suppress dissent.

This American mythology apexes clearly in the realm of sports.

Professional or amateur singers, even youth choirs belt the national anthem before every single match-up – from a national championship down to a game with kids barely old enough to drive, playing in a middle school gym.

Field-sized American flags and camouflage team uniforms become common decor.

Massive warplanes zoom over gargantuan stadiums, simulating the foreboding sounds people in lands Far Far Away might hear – blasts that would snap these people to fearfully scramble to duck under something, anything for protection. Meanwhile fans packed within these coliseums gawk at the fumes left behind, ogling at how impressive these sleek Vessels of Democracy are.

Writer Drew Lawrence once wrote, “Military Appreciation Night, it seems, is now every night.”

This has all been part of a process that spans decades, and it's no secret how much of it accelerated after 9/11. Former Air Force Lieutenant Colonel and writer Bill Astore once said “I think our military has made a conscious decision, and that decision was, as much as possible, to work with strong forces within our society. I think our military made a choice to work with the sporting world — and vice versa. I think that's something that's in response to 9/11." This notion is affirmed in Senator Jeff Flake and Late-Senator John McCain’s report on the massive financial ties between the Pentagon and professional sports leagues. Yes, broken clocks are somewhat correct every now and then (the Senators seemed more concerned with wasting taxpayer dollars, rather than the government exploiting supposedly “apolitical” sports to hypnotically recruit people to the military – or its efforts to whip up constant, even passive support and deference towards America’s every foreign policy decision).

Imagine how disruptive it would be, then, for an athlete to puncture this nationalistic blob. Of course, we don’t need to imagine what this looks like. There is a rich American history of athletic activism, and the tradition sustains to this day (a few scrolls through writer Dave Zirin’s work can give you a glimpse of this). Omar, in his own way, joins this rich history.

Nevertheless, myth and tradition draw boundary lines in American sports – of what’s normal, what’s allowed, and conversely what constitutes telling athletes to “shut up and dribble.” America’s patriotic lore pervades all corners of society, despite the incessant assurances that so many of these spaces are actually “apolitical.”

So too has lore justified Israel’s existence as an occupying force – a complicated, inevitable geographic puzzle, whose solving will, for some reason, inevitably displace and violate Palestinians who reside in the way. It’s not difficult to imagine how America’s self-asserted status as a guardian against a scary world – especially after 9/11 – interplays with this potential satellite dubbed the “only democracy” in the otherwise monolithically “dangerous” Middle East. Meanwhile, this supposed beacon occupies and violates millions of people’s rights, beneath a leadership ostensibly elected from a “democratic” structure.

But Omar exhibits a different kind of value in tradition – of the role one’s lineage can play to inspire and instruct. This approach could be what actualizes into something liberating, something transcending power-justifying mythos.

Omar’s story isn’t just about a tweet. Israel, like any entity using lore to preserve power and maintain good-standing, relies on stifling popular questioning of its status. And the power imbalances are clear. The significance of pushing against those scales expands beyond just 280 characters.

The Associated Press (again, whose office was flattened by Israeli airstrikes) fired young journalist Emily Wilder (a Jewish woman), in the wake of a concerted campaign by her alma mater Stanford’s College Republicans and other groups to punish her for expressing support for Palestinians in the past. Emily’s story contrasts starkly with New York Times columnist Bret Stephens. A frequent supporter of Israel in the paper of record’s pages, Stephens somehow neglected to disclose his side-gig at a pro-Israel advocacy group. But you can likely still expect to catch Stephens’ next column in the coming days.

The striking disparity of who is allowed to exhibit opinions and who is not embodies the power imbalance at play. Moreover, this shows how pervasive Israel’s mythos is, such that journalists even in America have seldom been allowed to question its status without facing repercussions; participating in the lore, however, bears no parallel consequence.

This disparity of course isn’t limited to journalism. Just years ago, Colin Kaepernick was blacklisted from the NFL after he kneeled during the national anthem, protesting systemic racism and police brutality. Now, as we’ve seen increasing power in numbers, athletes are able to express solidarity for the cause of racial equality in America, with less risk to their careers. But the scales are not quite at that level for the Palestinian cause – Omar’s outward support for Palestine is not joining a mass of athletes holding their fists up in solidarity. He is risking his athletic future.

But he knows that.

Omar Barakat joins a rich history of athletes bold enough to buck the mythical spaces of athletics. He joins a comparatively smaller – but growing – subset of people within sports speaking out against Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. In doing so, Omar is pioneering a new concentric circle of both histories, as he challenges layers of traditions and conventions, contrary to the power structures that have fashioned and utilized those layers. By looking for guidance from what came before him, Omar embodies a method that tries to translate tradition and myth into liberation and justice.

Perhaps Omar’s translation will be one passage of a broader narrative, constructed by the millions of voices across the globe who are eager to build a world of empathy, love, and solidarity for and between all people.

Hey there, before you go –

I hope you appreciated this article. If you did:

Share it with people you think oughta read it. Email, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram — wherever (find me on Twitter here!).

Subscribe for free. If you found this worthwhile, you’ll want to stick around.

Leave a comment below! This whole newsletter is concerned with people, and how we navigate and confront power & politics. How we are told a better world isn’t possible – yet how we can and do pursue one anyways. This project is enhanced with your thoughts, reflections, questions all coming together. I’d really love to see all your reactions turn into some good, solid conversation here.

Be well, take care, and love. A better world is possible.

Brave young man!

I have so much respect for him.